One thing that has been clear in the last decade or so is that the video game industry is just as inventive when it comes to imagining innovative games pushing the boundaries of the medium, as it is to find new ways of monetizing them and enticing players into spending ever more money. Some methods are more subtle and feel more acceptable to the public than others. But overall, monetization generated a lot discussion (and controversy) in recent years and the topic is more discussed now than ever before. As a matter of fact, we are entering a time where consumer spending habits are changing, and therefore, the standards for monetizing and making money in games are adapting to answer them. This is the first time in more than 20 years that the business model is experiencing such a shift, the last transition being from coin-operated arcades to retail and Premium. So obviously this is a significant change.

Many of these new models borrow from Free-to-play (F2P) – specifically from mobile games – and are becoming more common and prominent on console and PC. We heard a lot about loot boxes at the end of last year, but currently a new form of monetization is taking over: “games as a service”.

What you will learn in this post:

- Why GaaS looks like the next big shift in video game revenue model

- How time pressure and urgency are at the heart of its monetization system

- How it’s rooted in a profound change in players’ perception of value

- And why it could become the definite “win-win” model

- Why, on the contrary, “non-evil free-to-play” may still look like squaring the circle

- And what Shigeru Miyamoto and Nintendo have to say about it

Fortnite: A “free” game to rule them all

In March of 2018, just 6 months after its Battle Royale mode was first released, Fortnite became the biggest console Free-to-play game of all time – both in terms of revenue and monthly active players – thus surpassing previous record holder PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG). According to research firm SuperData, it generated $223 million in revenue that month. But it wasn’t ready to stop there. Just one month after that, the free-to-play brought Epic Games a whopping $296 million in revenues, representing a 32.8% monthly increase. Its growth has since been slowing down, but Epic still makes more than $300 million a month ($318 million in May) with the game’s slick monetization system.

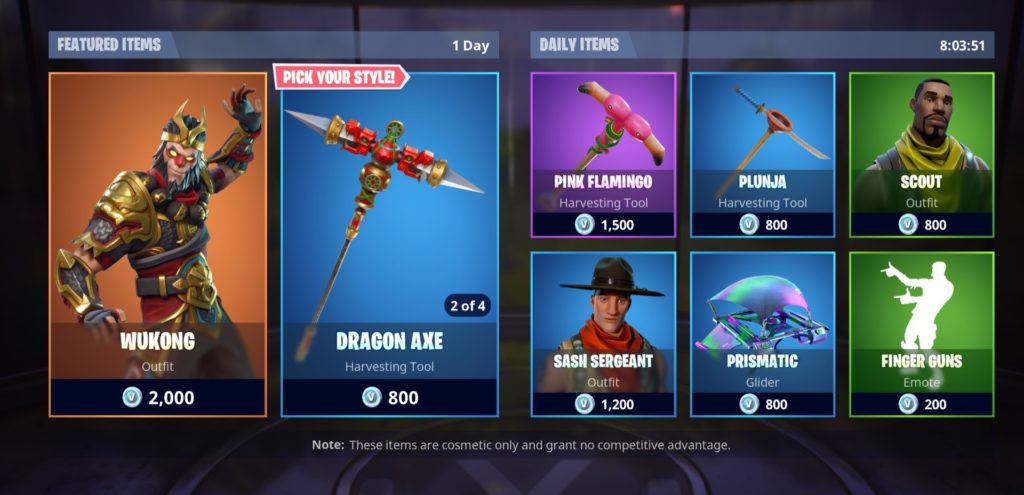

Fortnite generates revenue through two monetization mechanics: microtransactions and the latest hot trend in F2P called “Battle Pass”. Microtransactions allow players to purchase cosmetic items of their choice (character skins, emotes, dances…) rotating in the game’s shop. But the real money-maker is the Battle Pass, which gives players access to up to 100 tiers of rewards, including exclusive customization items, V-Bucks (the in-game currency) and XP boosts. This system was first introduced by Valve’s Dota 2 in 2013 but was really popularized by Epic and Fortnite. The game is based on a seasonal approach, where each season lasts about 3 months and comes with new content: customization items, weapons and gadgets, story elements, challenges, game modes and, of course, a new Battle Pass. During the season, players can either go with the free Battle Pass, but rewards are then scarce and only obtained every few tiers. Acceleration comes with the $9.50 premium Battle Pass, where they get rewards at every tier up to 100, or the $28 premium pass which comes with 25 additional tiers.

Fortnite is making this much money partly because accessing the best rewards require spending money, explains Pocket Gamer. This is why the game has the highest payment conversion rate of any free-to-play, according to them. But buying the premium Battle Pass is merely the beginning. Instead of completing the gameplay challenges necessary to level up – which requires a good amount of grind and playtime – they can choose to pay their way up the ladder and purchase tiers for 150 V-Bucks ($1.50) each. By the time players reach level 100, the Battle Pass provides just enough V-Bucks in return so they can purchase the next one, thus keeping them engaged for as long as possible. The more time they spend in the game and the more frequently they log in, the more they are exposed to the new skins in the shop. These, just as the Battle Pass, are accessible for a limited amount of time and rotate every day. This monetization system is designed to create a sense of urgency and get people to spend more. Making money is now all about engagement over the long term.

From the ashes of controversy

This trend of cosmetic-focused season passes comes as a replacement to “loot boxes”, the previous money-maker of the video game industry. Loot boxes, or “loot crates”, are packs of random in-game items that can be purchased with in-game currency or real money. With a rising use beginning in 2016, notably because of Overwatch’s immense success, loot boxes started being implemented in almost every major release of 2017, even in some single player games like Middle-Earth: Shadow of War. Because of their random aspect that borrows from gambling and takes advantage of psychological impulses to get people to spend more, they were already unpopular among players. So when EA took it one step too far with Star Wars: Battlefront 2 by offering items that granted significant gameplay advantages (pay-to-win) in an already fully-priced $60 game, an industry-shaping controversy understandably ensued. Many players swore never to buy a game using this revenue model, stating that letting loot boxes pass now would result in publishers and developers doubling down on this method.

What microtransactions, loot boxes and battle passes have in common is that they are all monetization methods borrowed from Free-to-play that are used in what is now called “Games as a Service” (GaaS). GaaS are games that, from their release, try to retain and keep players engaged for as long as possible through regular updates and new content addition. Games as a Service can blend these monetization forms with the Premium model, where the game is sold at a fixed price, although that is not necessarily the case, as Fortnite demonstrates.

A shift in consumers’ habits

This new model of Games as a Service emerged as a response from video game companies to consumers’ and players’ changing consumption and spending habits. In its report Defend Your Kingdom: What Game Publishers Need to Know About Monetization & Fraud, SuperData details how lower barriers to entry in the industry generated a fierce competition which in turn resulted in players expecting more for less from game makers. Players are becoming more hesitant to spend a large amount of money for a game they don’t know and are moving towards other options. “Consumers are less willing to pay $60 for a boxed game and instead choose titles with a steady stream of new content”, explains the research firm. “The shifting notions of value in the video game world have irrevocably altered players’ spending habits”, further develops Gamasutra.

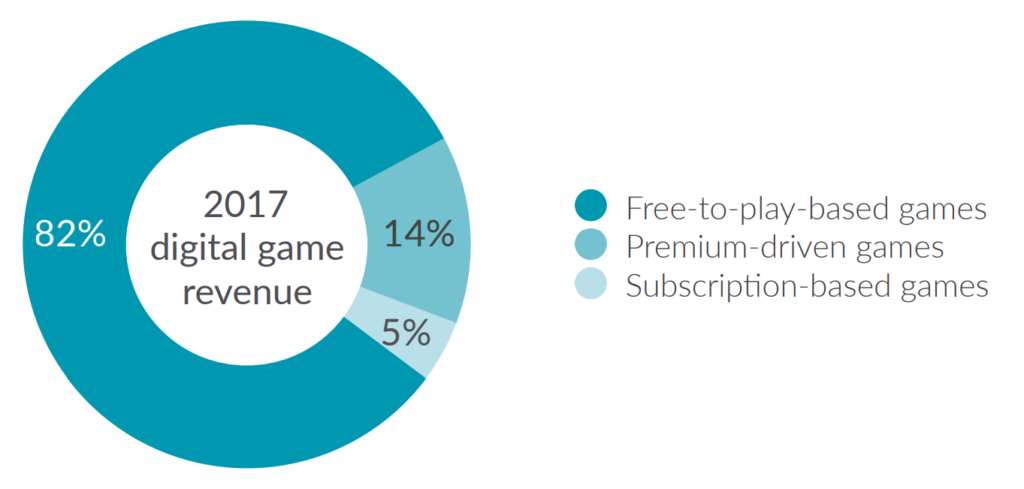

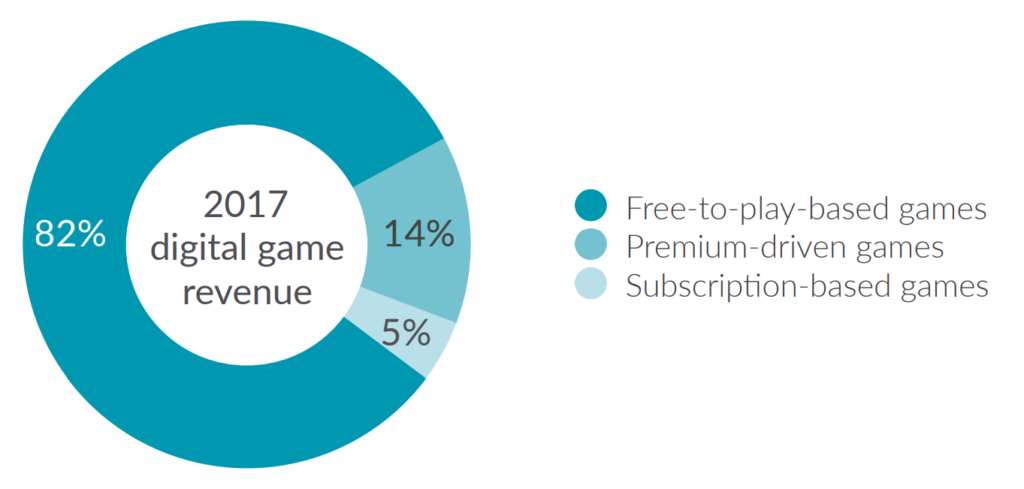

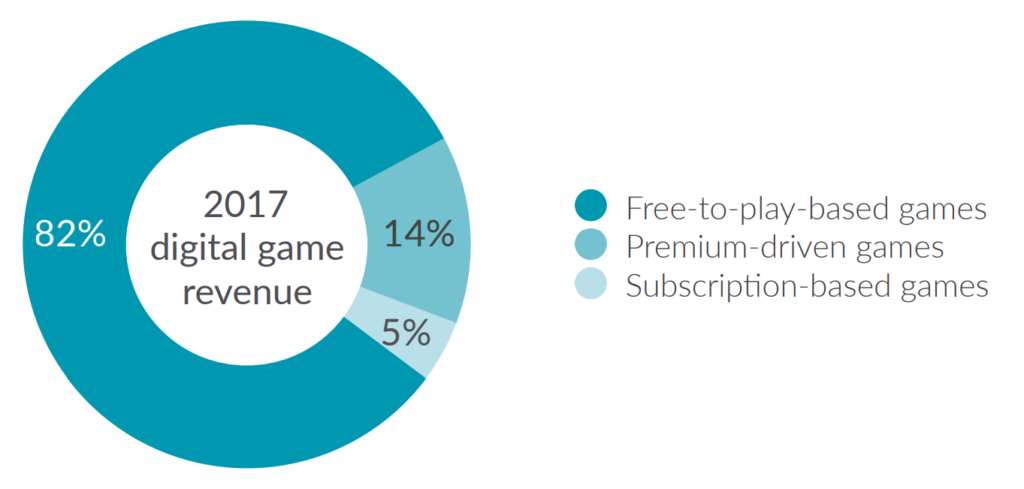

To meet these new expectations, publishers are taking lessons and inspiration from Free-to-play which in 2017 earned four times more than all other games combined (in digital revenues). “The top five grossing games of 2017 are all free-to-play”, according to SuperData. In addition, the report estimates that from 2017 to 2020, free-to-play revenues will drastically increase, by 47%, even as the addressable market is showing signs of saturation (audience growing by ‘only’ 14%).

For these reasons publishers adopted the Games as a Service model and chose to keep players engaged over time with regular updates. Because it mixes several revenue mechanics, GaaS caters to every type of spender, which seems to benefit players satisfaction notes the report. These hybrid models are growing and revenue per user is expected to grow twice as fast as the overall market. Video game companies earn billions more than with the old-fashioned approach of selling a one-time, $60 game, and as a result, SuperData estimates that Games as a Service “tripled the industry’s value”.

Games as a Service, yeah yeah!

When a new trend emerges or a business model is discovered, the same pattern tends to repeat, as history shows, and every company jumps on the bandwagon to capture some of the profit. This happened recently with loot boxes, a few years before with Online Passes and microtransactions, and now with Battle Passes and Games as a Service.

This time, because the fruit seems juicier and shinier than ever, every major game company is going head-first, praising GaaS and doubling down on the model. In 2017, Take-Two announced they “aim to have recurrent consumer spending opportunities for every title that [they] put out”. With microtransactions representing 42% of the company’s 2nd quarter revenues that year, CEO Strauss Zelnick believes in monetizing long-term consumer engagement.

Same goes with Electronic Arts, whose CEO Andrew Wilson says that “Games as a Service are reshaping our industry” and that “multiplatform experiences and subscription programs like EA Access are the future of this industry.” Square Enix, during a financial presentation, points out that “titles that have become global hits recently have tended to be offered via the ‘Games as a Service’ model.” As a result, the company believes this will become the standard for gaming in the future and “will approach game design with a mind to generate recurring revenue streams.”

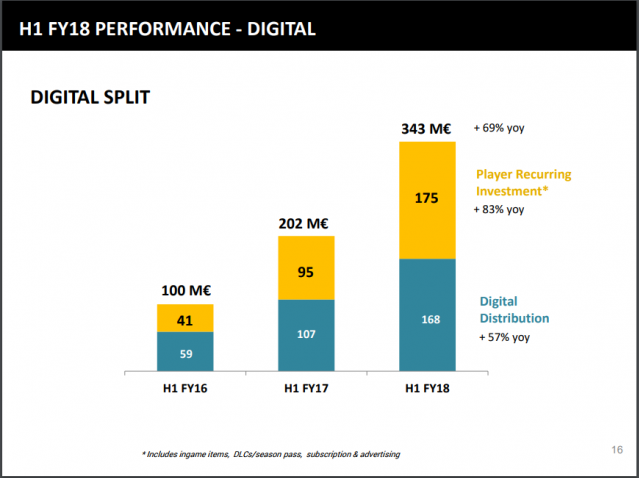

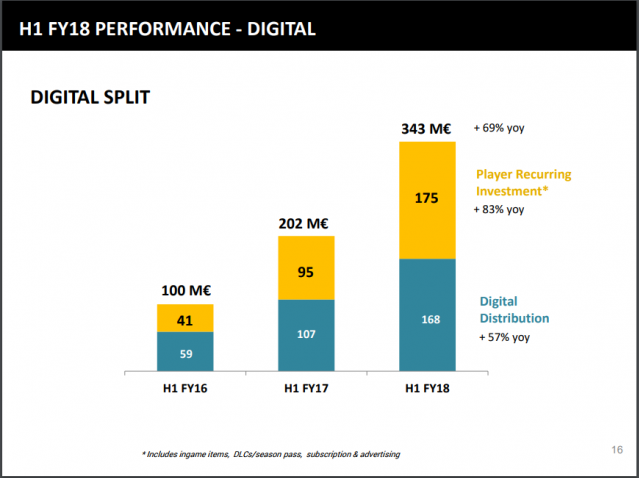

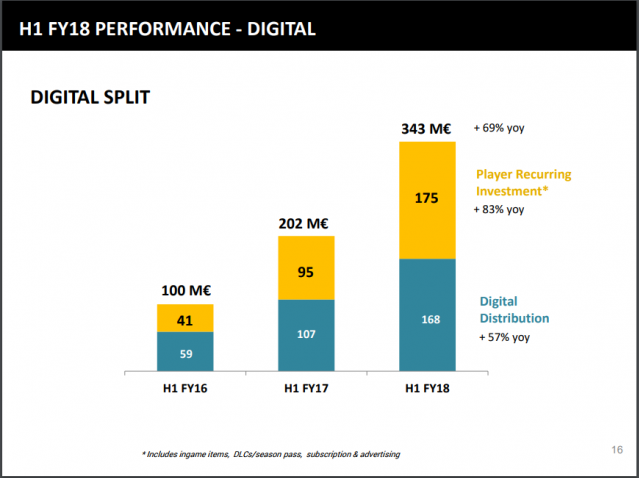

Finally, Ubisoft and its CEO Yves Guillemot offer additional insights as to why this new trend is taking over. It is more than just a shift in consumer habits. For the first time in the company’s history, microtransactions brought in more revenue than digital game sales alone during the first half of their fiscal year 2018. For this reason “we are transforming our games from standalone offline products into service-based platforms where we can continually interact with and entertain our players”, explains Guillemot. This is something Ubisoft has already been doing with games such as Rainbow Six Siege, released in 2015 and that it aims to keep going until 2028 by implementing new content. “Before, relates Guillemot, 80% of the sales were made during the first year, 10 or 15% the second, and 5% the third. Here, this is a completely different rhythm” which “allows to amortize the costs”.

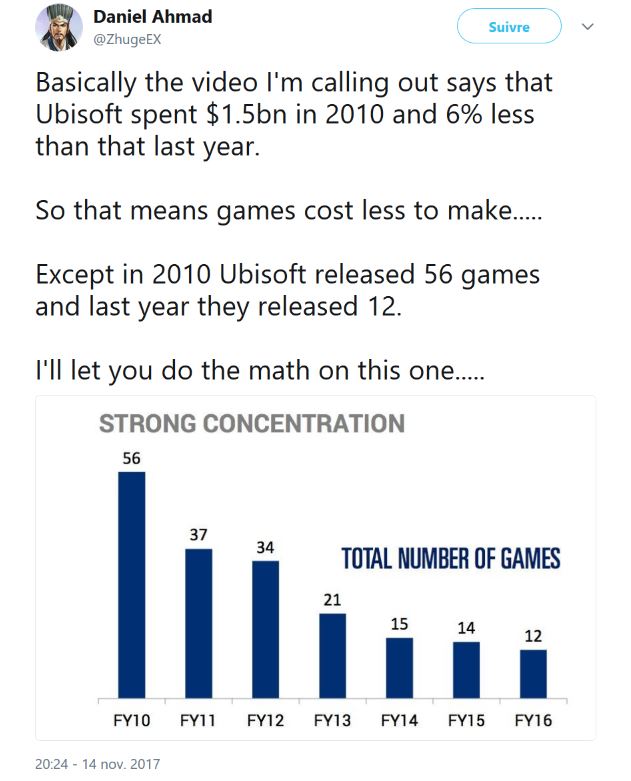

As a matter of fact, development costs exploded in recent years. As video game analyst Daniel Ahmad points out, while Ubisoft’s global development costs remain relatively stable each year, the number of games it produces diminished significantly. According to him, the company released 56 games in 2010, versus 12 in 2016, which represents a huge increase in development cost per game. This cost increase led video game companies to develop fewer games but also created a need for them to diversify their revenue models and imagine ways to make money over longer periods of time in order to amortize their expenses. The result is that sales at launch are now much less determining, as long as games manage to build and maintain a community over time.

Therefore, the objective for publishers is triple, explains French newspaper Le Monde. With Games as a Service, they aim at amortizing their growing development costs without having to raise the initial game price, responding to consumers’ changing habits, but also preventing the reselling of games and thus suffocate the second-hand market where only the resellers make money.

They previously tried to end reselling of games with Online Passes, following the lead of EA’s infamous ‘Project Ten Dollars’, but quickly ended up backing away when they faced heavy criticism.

It seems that this time the model is right, as the name “Games as a Service” suggests, because it is associated to a change in the legal status of the game. In this case, the game no longer belongs to the player who now merely pays the right to access it, just like a service. Thus, they can no longer resell it and companies like Gamestop, whose business model relies in big part on this, are seeing their value plummet.

Overall, GaaS is interesting because in addition to all the financial benefits it appears to offer for video game companies, it needs to satisfy players over the long term in order to function. “At a time where publishers depend more and more on a handful of games’ success, players have gained a lot of power”, explains French video game outlet jeuxvideo.com. Thus, games that want to succeed will have to satisfy players and shareholders at the same time, which has been pretty rare until now. If the name “Games as a Service” is not well perceived by everyone, because it often rhymes with DLCs and microtransactions, the majority of players seems happy with the model so far.

The risk of backlash keeps looming

If things are going well now, it may not always stay that way. As we have seen with previous trends – and loot boxes very recently – players have become extremely conscious about the constant pressure to pay more and many inside the industry have voiced their concerns regarding these practices. “The more games get into nickel-and-diming their players at every turn, the higher the chance of player burnout”, warns Jeff Gerstmann, editor-in-chief of gaming publication Giant Bomb. “It cheapens the entire experience”, he adds. Prominent indie figure Rami Ismail, from Dutch studio Vlambeer, believes “it’s almost impossible to do free-to-play in a non-evil way”. He is backed by Ryan Payton, from studio Camouflaj and designer on episodic game République, who qualifies F2P and its practices of “manipulative, evil and anti-consumer”. He talks about a “rush to squeeze as much money out of consumers as possible” and affirms he doesn’t want to take part in “manipulating people into spending hundreds of dollars for something that is clearly not worth it.” Even Owen Mahoney, CEO of Nexon Co., which pioneered microtransactions in South Korea two decades ago, warns about the unsustainable growth rate. “At the same time you’re monetizing, you’re driving users away – and then you have to monetize the remaining ones even harder”, he claims. He prefers to “be focused on quality”, arguing that “people are starting to finally realize the importance of longevity and bringing your customer back over time.”

This vision is also supported by legendary game designer Shigeru Miyamoto who urges video game companies to explore other ways to generate revenues, rather than F2P. According to him, Nintendo is thinking of different ways of charging players but is staying away from Free-to-play. “We’re lucky to have such a giant market, so our thinking is, if we can deliver games at reasonable prices to as many people as possible, we will see big profits,” he explains. He invites his peers to heed lessons from the music industry and its Subscription model, and believes in developing a “culture of paying for good software.”

“It’s necessary for developers to learn to get along with [subscription-style services]. […] When seeking a partner for this, it’s important to find someone who understands the value of your software. Then customers will feel the value in your apps and software and develop a habit of paying money for them.” – Shigeru Miyamoto

Players may quickly grow tired of being “nickel and dimed”, and we are never more than one mistake away from a controversy suddenly rendering a whole business model unacceptable to the public or simply forbidden. The loot box polemic last year, for example, gained so much traction that some governments regulated or even banned the model altogether. Just a few months back, in Belgium, paid loot boxes were declared illegal and Blizzard was forced to remove them from its games Overwatch and Heroes of the Storm in the country, thus cutting itself from its most profitable sources of revenue. When news are now surfacing about an Activision Blizzard’s patent describing “how machine learning could be used to entice players to spend more”, it seems that this risk still remains way too real. These practices, if they were implemented and brought to the public eye, could likely lead to another industry-shaping controversy.